Why should a progressive planner pay attention to the Spanish 15-M movement? One of its most complex and interesting aspects is its spatiality. Today, just a few months after the hatching of the spanishrevolution—a hashtag used by Twitterers to inform about the movement—the movement’s political content continues to be vague. The agenda fluctuates between a program that partially repeats old proposals put forward by the left-wing parties across the parliamentary spectrum in Spain and the ambitious but minority calls for self-government propounded by more radical groups. Perhaps the movement’s political positions will mature slowly in the future, however, the spatial practices of its camps and committees have proven to be a solid achievement, one of its more successful facets in promoting the spreading and organization of the protest. Combining social networks with temporary encampments, the 15-M movement demonstrates that activists can devise new uses of public space and new virtual political spaces through a collective, practice-oriented production of place.

Chronicle of the First Steps of the Movement

Following a series of preliminary actions during the month of April 2011, a demonstration was called on

Demonstration held on 17 May after the first camp was evicted.

(Photo Julio Albaran).

Sunday 15 May, one week before regional and local elections. It was a joint initiative by two recently created organizations: Juventud Sin Futuro, which involves university students protesting about the difficult economic situation suf- fered by young people in Spain, and Democracia Real Ya, a group with a wider spectrum protesting against the poverty and corrup- tion of Spanish politics, the virtual two-party system, the consensus regarding neoliberal economic reforms and the submittal of crisis policy to the whims of financial markets. The protest was a success, and almost 25,000 people took part in more than fifty cities. The demonstration organized in Madrid ended at Puerta del Sol, an emblematic square in the center of the city; minor disturbances broke out at the close of the meeting and twenty-four demonstrators were arrested. In protest against this and in order to demand their release, dozens of people set up a camp in the square and spent the night there.

(Photo pak)

The camp was broken up the next day by the police, which hailed the real start of the revolt. The eviction was spread on social networks and new actions were spontaneously called. That same evening, more than 5,000 people went to Puerta del Sol to make themselves heard and protest against the police intervention. The crowd continued to concentrate until late and a new, much larger camp was set up during the night. The crowds continued to gather and grow during the following days and the camp increased in size until it occupied practically the whole square, with new camps springing up simultaneously in Barcelona, Valencia, Seville and many other Spanish cities. The motto of Juventud Sin Futuro—“no home, no job, no future, no fear”— appeared to have taken root among the demonstrators.

Two days later, with the new camp in full swing. (Photo Pablo G. Albarraco)

Protesters faced an increasing police crackdown

and requests made by right-wing politicians to “clean up” the squares in the country.The judicial body regulating the ongoing electoral process banned demonstrations, based on its opinion that “it could influence the decision of voters during the elections of 22 May.” In response, the rebels chanted slo- gans such as “the people’s voice is not illegal.” As the days passed and the crowds continued to grow, the fear of a new police intervention waned. The crowds in Puerta del Sol and neighboring streets—which on occasions numbered 10,000— were too large to be stopped.

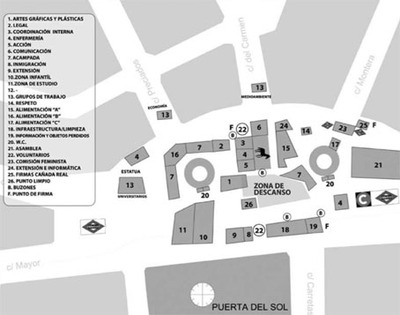

The day of the election arrived, but the repercussions of the demonstra- tions on the results were minimal. The right wing inflicted a historic defeat on the Social Democratic Party, which was hard hit by the economic crisis and abandoned to its fate by traditional voters due to its neoliberal reforms. The camps, however, continued to exist for another three weeks. During this time, the camp in Sol doubled in size, with the organization becoming more and more sophisticated and complex. Specific thematic commit- tees were established—international affairs, health, environmental af- fairs, education, cities, etc.—that made use of the adjoining streets and squares for holding assemblies. An initiative was set up to transfer the movement and debates to other districts of Madrid and cities in the metropolitan region —coordinated by the so-called Popular Assembly of Madrid—with a march to Madrid being organized from the most important Spanish cities. In view

of the increasing criticism by local traders and local and regional authorities—both in the hands of the Conservative Party—the General Assembly, responsible for coordinat- ing the decisions of the sub-assemblies within the movement, decided to dismantle the camp. They left an information point as a physical ele- ment of reference, symbolizing the occupation in the center of Spain.

The Spaces of the Movement

What were the movement’s spatial practices? What lessons can progres- sive planners learn from them? The 15-M movement produced places that were complex as a direct reflection of the plural, spontaneous nature of the movement. Although this has on occasions slowed the organization down, it is one of the reasons for its success and survival over time, helping it attract the attention of the media while also making it hard for politicians to understand the movement, establish links with it or suffocate it.

The most striking aspect of the spanishrevolution has been its ability to occupy public space and eradicate the mercantilization and alienation of the city’s central places for a prolonged length of time. The recurring slogan chanted during the concentrations, “this square is our home!” expresses this aspect. It is worth highlighting the functional and symbolic dimensions of this occupation. With respect to the former,

the occupation was open to many different types of people. Many were surprised by the heterogeneous nature of the demonstrators in terms of their social class and age—although this heterogeneity was not evident with respect to ethnicity and race, which is certainly worth reflecting on. Of course, traffic was interrupted or slowed down during most of the day, and although tourists continued to visit the square, the main force of attraction for them was to witness the event.

This led to protests by retailers, who lost clients, demanded compensation from the government and called for the camp to be evicted on many occasions. Instead, the zone has been used for a wide array of new processes, as the members of the camp and external groups proposed to carry out new activities which soon accompanied the concentra- tions and assemblies, for instance, a popular library, a nursery, theaters and an organic market garden.

On the symbolic plane, the occupation of Puerta del Sol, center of the city and country—the square is the origin of the main Spanish road network—has allowed it to occupy a prominent place in the lo- cal and national media. Logically, the press compared the occupation of Puerta del Sol to that of Tahrir Square in Egypt and later, the Syntagma Square of Athens. There are as many similarities between them as there are differences: while the occupations shared a common origin of a gradual deterioration

in the material conditions of social reproduction among the middle and lower classes, they differ in the extremely specific political contexts intrinsic to that social and economic deterioration.

However, beyond this obvious comparison, a deeper common thread is quite evident in these experiences. All three demonstrate the idea of Henri Lefebvre according to whom the right to the city is expressed, firstly, as the right to centrality, the right to occupy central areas, physically and in terms of the organization and circulation of power, taking the form of a revolutionary program that claims the self-government of public space.

Camp organization map.

Second, we should emphasize the massive use of virtual social networks, which has allowed the 15-M Movement to be everywhere before physically being anywhere or occupying any space. During May, considering only exchanges in Twitter in Spain, there were more than 580,000 messages related to the hashtags of the concentrations, submitted by almost 88,000 users. Even though these figures are significant, the most important aspect is their radically democratic role in mobilizing the movement and organizing it.This converted that period into an open process calling for all manner of actions by anonymous users, the eventual success of which was dependent exclusively on the conditions of opportunity on the course of events.

The camp’s library. (Photo José Maria Morenio Garcia)

The leading role of social networks has contributed to a third spatial dimension, the capacity of the movement to spread and break the conventional scalar regime. The movement has brought together more than seventy cities in a virtual space of common participation.

In the case of Madrid, the growth and internal organization of the camp took place at the same time as its assemblies expanded to other streets and squares in the city center and actions transferred to all the city districts and to other townships in the metropolitan region.

Organic market garden in the flowerbeds of the fountains. (Photo Gabriela Lovera)

This led to the revitalization and repoliticization of neighborhood associations, which after playing an essential role in the local democratic transition process of the 1970s, had been demobilized for many years. This simultaneous construction has decentralized the spaces of political activity, gradually doing away with conventional hierarchies. The direct consequence of regaining the right to centrality—the right to occupy the symbolic and functional heart of the city and rewrite its contents, the right to administer and distribute centrality—is the ability to subvert the social and scalar division of space. Although Sol maintained its symbolic centrality, its political bodies soon began to function on the same level as those established in a virtual forum, on street corners two blocks away from the square, in districts in a more remote part of the city or in a city in another part of the country.

When the center took on a different role with respect to other spaces, this was done for the purpose of accommodating and debating initiatives formulated in other places. Consequently, the center of the social space was projected as a non-differentiated site of political reception, and not as a stronghold of power from which decisions and rules emanate towards an eternally mute peripheral area.

This collective redefinition of the meaning of places and the way in which we relate to them could have a lasting effect on the manner in which we regard the city. In fact, those few days in May have served to encourage the building of new spaces of resistance and give new meaning to already existing initiatives in other spheres and areas.

Assembly of one of the thematic committees.

Conclusions

So what opportunities does the Spanish 15-M movement hold for reflection about urban planning?

The possibility and consequences of prolonged occupation of public space and the reorganization of its contents, outside the scope of established institutional codes.

The relationship of that occupation and organization with the massive use of virtual social networks as a new space for political activism and radical democracy.

The relationship between these networks and physical spaces and its ability to reshape and rescale social practices.

The capacity of persons to create new sites and identities related to them; in sum, to rewrite urban landscapes through a commitment to social justice, self-government and the deployment of common capacities, without being controlled by planned organizations or hetero-regulated participatory processes.

These dynamics suggest the need to review some ideals and guidelines assumed by progressive planners. We should pay attention to them

in establishing new criteria for comprehending urban and sociospatial phenomena and in collective efforts aimed at building spaces

of hope for social change and emancipation.

General Assembly. (Photo Adicae15M)