The history of a political current can never be reduced to that of its organisations or to the study of its doctrine, unless it has never had the least influence outside itself. On the other hand, it is difficult to identify such a current when it has not built any permanent organisation and has not produced a body of doctrine. Nonetheless, it is the premise of such a current that we beg to offer as a research topic based on the story of an activist publisher from the 1930s on.

What is surmised here is that at certain periods of French contemporary social history, and probably elsewhere in Europe, a political current has sprung up that overcomes the historical deadlock between the protagonists of “State socialism” and those of “socialism without a State”. This current has not given birth to permanent political organisations ; it has not spawned recognized theoreticians, it has not spelt out a formal doctrine. The reason that suggests itself for those three negatives is that this current has only emerged in periods of social upheaval and has generally lacked time to create a lasting political vehicle, and that the theory of what it stood for could only develop after the event.

As shorthand, we will designate this current as “libertarian socialism”. This label has no historical legitimacy ; it has been used by Daniel Guérin as cover title of his first collection of essays aimed at reconciling those he called “twin brothers, feuding brothers [1]”. In later editions, he changed it to “libertarian Marxism”, and then to “libertarian communism”. But at the time when, in our estimation, that libertarian socialism first materialized, libertarian communism was claimed as their objectives by the Spanish CNT and FAI, and they are clearly different.

We propose to search for that current through the enduring story of an unusual publishing house, which has carried on for fifty years thanks to the exertions of one individual, René Lefeuvre, and which has outlived him. The features of that publishing endeavour – the Cahiers Spartacus – qualify it as an appropriate tool for identifying that current and turning it into a legitimate research topic :

– It is an activist publishing house, i.e. one that pursues specific political goals.

– It is not-for-profit, and has no other concern than to publish whatever it feels should be made available to the readership it hopes to reach.

– It is independent, to the extent that it is not controlled by any political organisation.

– However, it does not rely on patronage or to any significant extent on donations. Therefore, while it does not need to be profitable in any sense, it can only carry on publishing if there are enough buyers for its output. This has not always been the case.

Libertarian socialism as we mean it only materializes as a political current after the October revolution. The lessons it draws from the 1917 revolution and its aftermath differ from those drawn by other anti-Stalinist currents such as anarchism, the Trotskyism or even the council communism, experience of this latter was anyway practically unknown in France at the time. Its political assumptions may be summarized as follows :

— The evolution of society can only be grasped through the analysis of class struggles ; class antagonisms, crises borne by the ruled can only be eliminated if they wrest political and economic power from the ruling classes and exert it themselves.

— The capitalist State is the instrument of domination of the ruling classes ; as such, it has to be dismantled ; but as classes will survive even after such dismantlement, and as social activities will need to be organised and decisions made, political institutions will remain necessary at various territorial levels.

— The nation is the framework of bourgeois power ; it is not suitable for building socialism ; libertarian socialism is internationalist by nature.

— Libertarian socialists know that trade unions have become institutions of capitalist society ; they find however that in many instances taking part in union activity is the first means at the disposal of workers to take part in collective action and the class struggle.

— Political parties are necessary to formulate analyses and proposals, to gather means for education and action ; but no party can claim a monopoly of power :

“The dictatorship of the proletariat cannot be implemented by a single sector of the proletariat, only by all sectors, without exception. No workers’ party, no trade union can exert any dictatorship. [2]”

Lastly, libertarian socialists do not view taking part, or not taking part, in the electoral process and discharging elective duties as a matter of principle. But for them, for any party coalition to obtain and retain government power through the electoral process cannot be a goal in itself.

An activist publisher

At the request of his father, a master stone mason in a village in Brittany, René Lefeuvre also became a stone mason. But rural life did not suit him. Although with only primary schooling, he was an assiduous and inquisitive reader. At 20, when called up for military service, he managed to be quartered in the Paris area, where, but for the war years, he will lived from 1922 to his death in 1988.

By what he had learnt of it, and in spite of the repulsive picture drawn of it by the conservative opinion leaders in his home region, he wss attracted by the Russian revolution and the achievements of the Soviet Union. He read Boris Souvarine’s Bulletin communiste, which reported on them but could not hide the disputes that are started to divide the Executive of the International, of which he was a member, and the leadership of the Soviet Communist party. Boris Souvarine’s exclusion from the French communist party, of which he had been a founding member, and Souvarine’s maturing understanding of the class nature of the Soviet regime contributed to René’s political beliefs : availing himself of the notions of classes and exploitation as developed by Marx, Souvarine asserted in the late 1920s that a new ruling, exploitative, class was being created in the Soviet Union through its control of the State. He also rejected what he saw as the invention by the Soviet leadership of a Leninist doctrine. Lastly, he also rejected what he perceived in Trotsky – whose right to hold dissenting views he had supported in the Executive of the International – as a commitment to reproduce the analyses and behaviour of the Soviet Communist party. [3] René attended some of the meetings of the Cercle communiste Marx et Lénine launched by Boris Souvarine in 1926 with other members or former members of the CP opposition. In 1930, it became the Cercle communiste démocratique, whose purpose was to “uphold, continue and invigorate the democratic and revolutionary tradition of Marxism” and to “actively seek the seeds of the renewal of revolutionary thought and action”. Its manifesto expanded on the theme : “Together with Marx and Engels, the Cercle declares itself democratic, by which it meant to restore — against fake communists, who negate it, and fake socialists, who debase it — a notion which is inseparable from the revolutionary idea. Communists and socialists of the Marxist school in politics had long simply called themselves ‘democrats’ before calling their party ‘social-democratic’. The Marxist critique of the implementation of the democratic principle in capitalist society is directed at the contradictions of its practice, not to the principle itself, and makes the point that it is impossible to achieve true political democracy without the foundation of economic equality. [4]”

Until 1928, René earned a living as a stone mason craftsman. Then, thanks to distance learning courses he took up when in Brittany, he was hired as a clerk in a claddings firm, which frees some of his time to pursue other interests. This is when he joined the Amis de Monde, and became its secretary. Launched in 1928 by Henri Barbusse, a Communist party member since 1923, Monde [5] sought to be “a weekly publication, reporting major literary, artistic, scientific, economic and social information to provide an objective picture of current affairs”. But its launching reflected a disagreement between Henri Barbusse and the Communist International of the third period, in which the social-democrat, now dubbed “social-fascist”, had become the main opponent. In 1926, the International had requested Henri Barbusse to launch an international body of revolutionary writers. As this would have only brought together Communist party members, or writers already close to the Party, Barbusse chose instead to create “a hive of publications” – much more than a newspaper – aiming at a “world gathering of intellectuals” [6]. Contributors to Monde would therefore include Communist writers, some of them writing from the Soviet Union, but also former Communists and even Socialists, for this Monde will be condemned at the second congress of revolutionary writers held in Kharkov in November 1930. Monde was charged with being “a paper without guiding principles, which from the start has taken an anti-Marxist position”, of being distinctive by “its confusionism”, of harbouring contributors who are “Trotskyist agents, social-fascists, bourgeois radicals, pacifists”, in short with being hostile to proletarian ideology. It is worth mentioning that back in April 1930, Pierre Naville, Trotskyism’s first official representative in France, had taxed Monde in his Lutte de classes with being a “collection of garbage from the most swampy, the most confused, and in the end the most anti-proletarian output of petty-bourgeois politico-literary circles.”

Monde was clearly not a Communist party paper, although Henri Barbusse would not condone attacks against the Soviet regime. The Amis de Monde were assigned ambitious goals : not only should they support the paper’s sales, but they should also contribute news and reports to it. In 1930, when René Lefeuvre became their secretary, the membership numbered about 800. Lucien Laurat [7], who belonged to Monde’s editorial team, organised a political economy study group, which in particular studied Marx’s Capital. As the Amis were keen that other groups, on other topics, be set up, René dedicated himself completely to the task. Always eager to learn, he was also devoted to the transmission of knowledge, to popular education which will always remained the true aim of his publishing. New study groups were set up : for social studies, workers’ movement history, architecture, Esperanto ; also a drama troupe. René also organised movie screenings and visits to exhibitions.

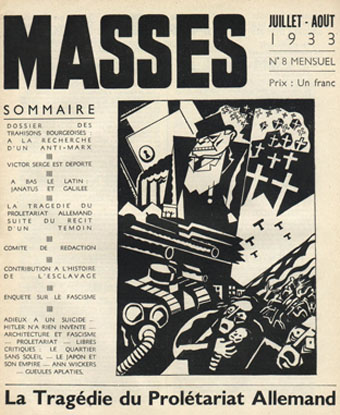

After two years, members of the study groups were asking for a means to publish regularly the outcome of their work. René was put in charge of that venture. He suggested Spartacus as title of this new paper : members choose Masses, a reference to the American New Masses.

At first, Masses’outlook was not significantly different from that of Monde and the manifesto published in its first issue, dated January 1933, states in particular that “a revolutionary culture is opposed to bourgeois culture. In the great struggle, such a culture is a weapon” ; and also that “against bourgeois calumnies, we will defend the Soviet Union’s exertion to build a classless society by setting truth against lies.”

Events made Masses partly change its editorial course. This first issue did indeed include features on architecture, sociology, the theatre, and on workers’ unity. In the second issue, there’s also a piece from Rustico [8] in which he reports on the activity and state of mind of the Berlin Communists he joined in October 1932 in expectation of a decisive showdown in Germany between reactionary forces and the masses. The third issue, dated March 1933, pays tribute to Karl Marx for the fiftieth anniversary of his death, with, among other items, the beginning of a summary of the main thesis of Rosa Luxemburg’s Accumulation of capital. Masses is a 20-page monthly, of medium format, with a fairly sophisticated layout and some pictures, particular care being lavished on the front cover.

Contributors to Masses were in their great majority young members of the study groups. But the editorial staff quickly changed : in May 1933, Masses briefly quoted an announcement from the Cercle communiste démocratique that Victor Serge, who had been living in the Soviet Union since 1919, had been arrested. He was among the writers who supported Monde. In July, Masses publishes a letter from Victor Serge in which he spells out the principles of his opposition to the regime. René Lefeuvre requested “that authorized sources inform the Western proletariat of the reasons which justify Victor Serge’s punishment and why he has been refused for so many years the passport he needs to leave Russia”. Compared, for example, to what the Cercle communiste démocratique was writing at the time, this is very moderate indeed. The same issue includes a new report from Rustico, on those events in Berlin which, from January to March 1933, led to the Nazis’ victory, the outlawing of the Communist party and the repression of its members. Masses did not publish the letters in which Rustico takes to task the leadership of the Communist party and of the International. Nevertheless, this was more than the contributors to Masses who were Communist party members could take. In a communiqué published by l’Humanité, the Party daily, they question the stand taken by Masses in favour of Victor Serge, against, according to them, the opinion of the editorial board, and also the “controversy about events in Germany” and warn readers “that the Masses periodical was bound to become a tool in the hands of counter-revolutionaries”. They were compelled to leave the editorial board.

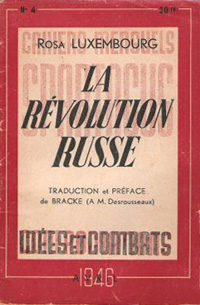

New contributors made their appearance in the following issues. They were former members of the Left opposition of the Communist party, some of them quite experienced, like Marcel Body [9]. And as Masses had initiated an inquiry on German fascism, Kurt Landau gave his opinion, as do spokesmen for the SAP and for German communist workers groups, heirs of the council communists. Masses is much less a product of the study groups, and more of a meeting place for activists looking for answers to the challenges of the times. Current affairs, including debates within the SFIO (the French socialist party), and theoretical insights take pride of place. In January 1934 – the fifteenth anniversary – Masses publishes Rosa Luxemburg’s last newspaper piece and Karl Liebknecht’s last speech. In May 1934, as it had done for German fascism, the editorial board launched an inquiry about the dictatorship of the proletariat and democracy, with an excerpt from Rosa Luxemburg’s The Russian revolution as a primer. Amilcare Rossi [10]’s contribution to that debate was published in the next issue, the 18th, in June 1934. But other contributions, if they have ever been written, will not be published : in issue number 19, which is the last, it is announced that they will be the material of a special issue, which has never appeared.

René Lefeuvre had to interrupt publication Masses because, having lost his job, he could no longer meet its costs. The Amis de Monde suffered from the split between the Communists and their opponents. Monde itself, initially flourishing in its first two years, now faced difficult circumstances. In addition, René was now committed to a new environment : in August 1934, with other contributors to Masses, he joined the Socialist party.

It is at first sight surprising that revolutionaries, steeped in Marxism, should join such a party, with a significant industrial worker membership in only a few parts of France, and focused primarily on elections. But the SFIO had experienced a number of shocks over the preceding few months : it had renounced its alliance with the Radicals, who now participated in a government of National union. Its right wing had been expelled, but the debate it had started on the subject of planning led the Party to consider an action program. Its left wing, the Bataille socialiste, led by Jean Zyromski and Marceau Pivert and in favour of joint action with the Communists, had lost the out-and-out pacifists among its supporters. Feeling it had to race against the fascists, it started to develop new organisations and new methods : youth movements, uniformed self-defence units, action groups, new propaganda media. In addition, Trotsky had ordered his French followers, the Bolshevik-Leninists, to join the SFIO, which they did during this same month of August 1934.

But it is the bloody events of February 1934 and their aftermath that convinced René and his comrades to join the socialist organisation. On the morning of 6 February, the day of the right-wing anti-parliamentarian demonstration and riot, Marcel Cachin was writing in the Humanité : “One cannot struggle against fascism without struggling also against social-democracy.” If, on 12 February, left-wing activists had gone on strike and demonstrated jointly it was not due to the national leaderships of the parties. The Bataille socialiste, for its part, was clearly in favour of joint action. In May 1934, the Communist International changed tack and declared in favour of a united front with the Socialists. On 27 July, an agreement was signed by the two parties. Aimé Patri [11], in the last issue of Masses, may be mistaken about the reasons for this change when he wrote : “It is the French working class, by demonstrating spontaneously and through its deeds that it aspires to unity, which has obliged the Communist International as well as the French section of the Labour and Socialist International to act accordingly.” However, for the activists, there is now a real prospect of efficient action on the ground, in joint committees.

In putting together Masses, René Lefeuvre had been trained in publishing techniques by the typesetters, and he was now able to earn a living also as a proof-reader. In December 1934, with members of the last team at Masses, he launched a new weekly : Spartacus, for revolutionary culture and mass action. It was said in its first issue that Masses would continue, but only as special issues. The first of those specials – indeed, the only one – is a brochure on the Berlin Commune of 1918-1919, the work of André [12] and Dori Prudhommeaux. It is made up mainly of the Spartacus League’s program and of Rosa Luxemburg’s speech on that program. For René, it was of primary importance to disseminate the political writings of Rosa Luxemburg, that had not been widely translated and published in France. This concern is clearly apparent in the articles published in Spartacus.

André Prudhommeaux, briefly a Communist party member, had been active in 1929-1930 in the “Groupes ouvriers communistes”, inspired by German council communism, entertained a relationship with Karl Korsch and rejected the Leninist view of the party. He had been to Germany and had brought back documents. In 1930, his Librairie ouvrière, in Paris, had published as a brochure a French translation of Herman Gorter’s 1920 Open letter to Comrade Lenin in which he objected to the tactics foisted upon Western communist parties by the new International. In 1933, he was one of the French organisers of the committee for the defence of Marinus Van der Lubbe, who had set fire to the Reichstag. The collapse of the German workers’ movement caused him to reject Marxism and become an anarchist. From1936, he was very active in defence of the Spanish revolution, even if he grew critical of the CNT taking part in government. A publisher and printer (based in Nîmes, he launched a printing co-op) as well as an activist, he provided René with material and practical advice, and sometimes loses his temper when René appeared to be too slow in making use of both.

Spartacus did not last as a weekly ; in April 1935, the masthead of issue number eight recognizes that it is at best a monthly. The last issue, the tenth, was published in September 1935. It had only four pages and was devoted to to the exclusion of the Trotskyists from the Socialist Youth, to which it objects and asks instead for the Youth to be made autonomous from the national party leadership.

In May 1935, France and the Soviet Union entered into a pact of mutual assistance. Stalin “understands and fully approves the policy of national defence pursued by France”. The Communist party quickly fell in line with the new policy of the International and reclaimed the Tricolour and the Marseillaise. The prospect of a new Union sacrée which, in 1914, had being instrumental in sending the people to the slaughterhouse, looms again.

This new political scene deepened the ongoing disputes within the Bataille socialiste. About unity with the Communist party, about national defence, about activism, Zyromski and Pivert differed significantly : Pivert was against a potential merger with the Communist party ; he rejected national defence in a capitalist society. In October 1935, Marceau Pivert sought to unite left-wing groups within the SFIO and launched the Gauche révolutionnaire, which is defined by what it opposes and by a prospect – that of the socialist revolution – more than by a doctrine, which was yet to be developed. It merged a number of small groups, among them revolutionary socialists who had been expelled from the SFIO because they were in favour of joint action with the Communist party, the group around Spartacus, and also former Communists. Above all, it attracted the younger, more active members of the SFIO.

This new tendency published a monthly bulletin of the same name, La gauche révolutionnaire, and René Lefeuvre was put in charge of it. He also took charge of the trade union column, at the very time when the CGT was reunited.

René sought to resurrect Masses by replacing items about internal party matters in La gauche révolutionnaire by pieces about doctrine or the history of the workers’ movement, but this was received unfavourably by some of the readers. Back in 1934, he had defined a publishing program aimed at “providing the proletarian masses with ideological weapons and prepare them for the struggle in all areas” : a periodical like Masses, but issued more frequently, providing more reports on daily struggles and more attractive in layout ; brochures in which current issues would be dealt with in more depth ; and brochures of revolutionary history. It is to the second leg of this program that he would henceforth devote himself. Not only urgent needs had to be addressed, but the Librairie du travail [13], the publisher which, for the past twenty years, had been an anchor to revolutionaries, was in dire straits. It would cease to publish in 1937.

The subject matter of these brochures, the Cahiers Spartacus, sub-titled “new series”, was indeed of some urgency : reports on the soviet regime, the prospect of a new World war, the support to be provided to the Spanish revolution.

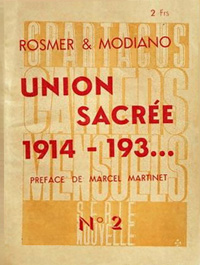

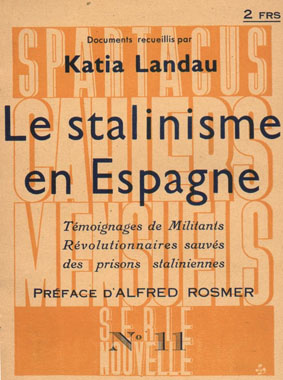

The first Cahier Spartacus, published in October 1936, bears as cover title 16 fusillés, and Où va la révolution russe ? as sub-title. It mainly consists of writings by Victor Serge, who had been freed at last and who returned to France during the summer. In the first of them, he reports on the most spectacular of the Moscow show trials, which had led to the execution of Zinoviev, Kamenev, Smirnov and other Bolshevik leaders. Two other writers contributed articles against France’s policy of “non- intervention” in Spain, in particular against the government’s refusal to supply weapons to the Republicans. The next brochure, in November, had as its title “Union sacrée 1914 -193…”. It consisted mainly of excerpts from Alfred Rosmer’s essential Le mouvement ouvrier pendant la guerre, that had just been published by the Librairie du Travail. Also included are pieces on trade union unity and collectivisations in Spain, reproduced from L’Espagne socialiste, the French-language paper of the POUM, to which la Gauche révolutionnaire felt close ; and also brief reviews of Souvarine’s Staline, un aperçu historique du bolchevisme and of Trotsky’s La révolution trahie. The following month, under cover of the Cahiers Spartacus, was a brochure by Jean Prader [14], Au secours de l’Espagne socialiste, also published by the Librairie du Travail. René Lefeuvre added to it the authorization he received from Marceau Pivert, as Prader criticized the Gauche révolutionnaire’s stand on the matter of arms supply, and also a warning call signed by Julian Gorkin, of the POUM’s international secretariat, about the crimes that the Stalinists were about to commit in Spain. In his brochure, Prader not only discussed the pros and cons of the policy of “ non-intervention” and gave his own views ; he also dealt in painful detail with the question of how revolutionaries should respond should war break out, a conundrum that was going to undermine them over the next few years.

The next brochure was the first French edition since 1922 of Rosa Luxemburg’s The Russian revolution in a new translation by Marcel Ollivier [15]. Next would come the Gauche révolutionnaire’s program and its response to the threat of dissolution it faces from the Party leadership, and, in March 1937, the writings on revolutionary Catalonia published at the same time by André Prudhommeaux in his Cahiers de Terre libre : a report by André and Dori Prudhommeaux on the arming of the people in the Spanish revolution and their translation of Was sind die CNT und die FAI ?, written by the DAS Gruppe in Barcelona to try and counter Stalinist propaganda in the workers’ movement. In June, the Cahiers Spartacus released, under the title Le Guépéou en Espagne, Marcel Ollivier’s report on the May 1937 events in Barcelona. By November 1938, René had published fifteen such brochures.

Until then, René Lefeuvre and his comrades had practically never met the anarchists and their doctrines. Rosa Luxemburg, in her pre-war writings, had nothing but harsh words for them. René had found them hard to fathom ; their groups were fairly closed. It is the recognition of the committees of the CNT’s leading role in the early months of the Spanish revolution and the necessities of international revolutionary solidarity which made René distribute those writings. In 1938, he distributed another Cahier de Terre libre, a collection of Camillo Berneri’s Spanish writings.

Growing disagreements between the majority of the SFIO and the Gauche révolutionnaire led to the dissolution of the latter in April 1937. René then took charge of the Cahiers rouges, the new monthly of what was henceforth an unofficial tendency. At the Royan congress, in June 1938, the tendency’s leaders resolved to leave the SFIO and launch the Parti socialiste ouvrier et paysan (PSOP). For René, and he was not alone, this was an admission of failure, as the new party only attracted a minority of the erstwhile supporters of the Gauche révolutionnaire, whose influence was still growing. The PUP [16] having joined the SFIO after the 1936 parliamentary elections, the PSOP became the French member of the International Bureau for Revolutionary Socialist Unity. In September 1938, the Bureau launched the International Workers Front against the War, which advocated a policy of revolutionary defeatism. But, as Prader had remarked in an issue of Spartacus, this policy, which Lenin had been promoting in the First World War, did not prevent war.

René Lefeuvre was in charge of the PSOP’s weekly, Juin 36. In January 1939, he started a new Masses, of which three issues were published.

At the time of mobilization, and in spite of having being sentenced to six months in jail because of his role in the PSOP, he was called up. He was eventually taken prisoner and as such spent five years in Germany.