Are you waiting for the Revolution ? Well the time is right, because the long-awaited financial collapse has already happened. All we have to do now is wait for the social and political consequences.

Just kidding ; we know it’s more complicated. After all, the working class has to be politically conscious, and that means being aware of its historical role as the bearer of revolutionary change in the form of a new mode of production and social relations that preclude domination and exploitation. Yet, wherever you go, the workers—the proletariat if you will—seem to be far from realizing this destiny. In fact, they could be further from it than almost any other group.

But I’ve just seen a film that somehow inspires a strange kind of optimism, even if working people quite rightly place little confidence in those who would push them onto the front lines of social combat. No, it isn’t Ken Loach’s Looking for Eric (2009), although his glorification of collective working-class action is certainly thought provoking. After all, who would have thought that a group of elderly soccer fans led by an ex-Teddy Boy had the potential to carry out the efficient commando operation that is the movie’s climax. But Loach’s film is a fantasy about a soccer star (Eric Cantona). And the idea that spectator sports can somehow weld unique social bonds, a new expression of proletarian solidarity, and then lead to direct action in the defense of the humble and down-trodden is not optimistic ; it is fantastic.

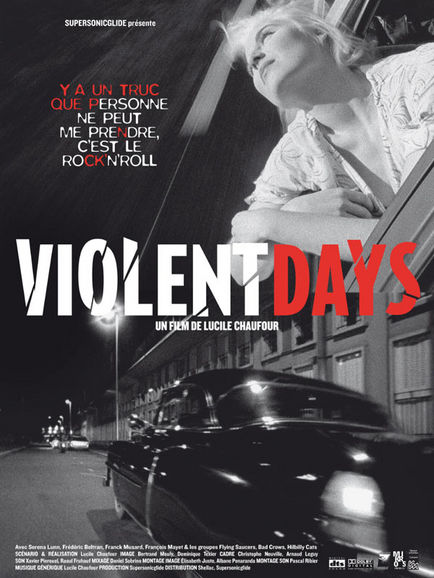

The film I’m thinking about is Lucile Chaufour’s Violent Days (completed in 2004, but just now released). Here, strangely, the working-class element is exactly that depicted in Loach’s Looking for Eric, that is to say the working-class subculture of rockers. Yes, rockers, those people out in the cultural wasteland somewhere, who still believe rockabilly, or rock ‘n’ roll, or rock, or whatever you want to call it, is the pinnacle of rebelliousness. Nothing new. Ever since Blackboard Jungle (1955) and Rebel Without a Cause (1955) right up to This is Spinal Tap (1984) and Todd Haynes’ The Velvet Goldmine (1998) or I’m Not There (2007) we’ve had to put up with the celebration of sex, drugs and rock and roll in one form or another.

But Chaufour goes further. She shows how rock and roll music has, at times in recent history, represented a window onto working-class mentality in all its dimensions : social, gender, aesthetic. Watch this film, and you understand the potential for violent rebellion possessed by working-class people.

In any case, this is the story. After a night of drinking, a young couple and two male friends leave in the morning for a coastal city to attend a rockabilly concert. Once there, they drink and disperse, allowing us to observe the scene, which finishes early the next morning with a whimper, but not after a rather brutal fight between rockers and local gangs. However, this fight happens outside the shabby concert hall, and hardly anyone is aware of it.

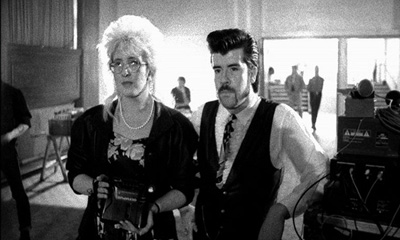

The unique thing about this film is that the story, essentially about the relationship between the young couple, is placed within a carefully constructed context of labor, love and desperate living. Lucile Chaufour films—in a grainy black and white—the protagonists at their different work places, interviews different couples with their children talking about their lives and (limited) aspirations. It’s like a combination of Diane Arbus’ photography and Barbara Koppel’s Harlan County U.S.A.(1976), except that Chaufour gives us much more to analyze.

Firstly, she shows how rockabilly and much rock and roll is music that reflects and stimulates aggressive behavior. Simply observing the relation between driving a car and the driving rhythm brings home how speed, risk taking and nihilistic bravado is an expression of proletarian mentality. Drugs, and here beer is the drug of choice, can be placed in the same category. Getting smashed and then risking getting smashed in a crash is the kind of self-destructive behavior that working people have always been encouraged to exult in. Taking it to the limit, racing with the devil, as Gene Vincent put it, is the ultimate kick.

But there is also fighting. Alan Sillitoe’s novel Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1958) is the best literary evocation of this working-class pastime, and for sheer emotional tension Chaufour’s film can’t be beat. Her graphic docu-fiction is the closest thing to being there we can get. The senselessness and brutality of modern day, proletarian “honor” vendettas is a high few “bourgeois” people can appreciate. With this film, you can appreciate not being there at all. Between rockers and homies, only the outward symbols and the available weapons have changed.

The problem is that this working-class culture is infused with consumer values holding-out the false promise of some sort of material liberation from social domination. But we see that family life for proletarian people still features early marriage and childbearing, indebtedness, domestic violence and arrested development of all kinds. And we might as well go back to the original meaning of “proletariat”—Ad prolem generandum : those people without property who reproduce in relatively great numbers. Their condition does not permit equal or healthy conjugal “relationships”, “planned parenthood” or mature childrearing.

Violent Days puts it right in our faces. The Romans during the late empire were more-than-apprehensive about the uncontrollable political potential of this class of people. Even bread and circuses sometimes were not enough to keep them in line.

The bad news is that Lucile Chaufour’s film is in French. Moreover, this impressive analysis of working-class culture is based on interviews and study of French rockers, who for the past fifty years have been assiduously replicating the experiences of alienated U.S. and British, working-class youth. The “globalization” of capital has, slowly but surely, “globalized” the culture and sub-cultures we know so well.

But no matter, the film may be released soon in English speaking countries. If it is, it will be far more useful in understanding popular uprisings than the innumerable popular culture studies by academics, who forget how thwarted intelligence and energy is the great political unknown in any situation of economic “crisis”. “Violent Days” may be here again.